Copper refining requires putting mined rock through several processing stages. Here’s an overview of how that happens.

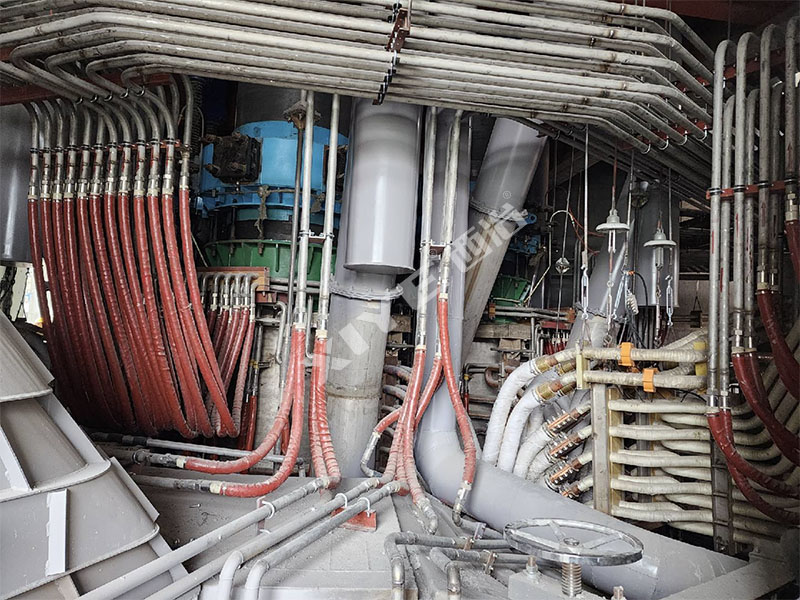

Mined rock typically contains less than 1 percent copper. That means to become a market-ready copper product, it must undergo a variety of physical and chemical processing steps. Silicon-manganese smelting furnace

After copper metal is mined by a company, the first major step in copper refining is concentration. This crucial process, which is generally conducted at or very near mine locations to save on transportation costs, involves grinding mined ore to roughly separate copper from waste rock.

The copper is concentrated further by slurrying the ground ore with water and chemical reagents. In this process, air is blown through the mixture, and the copper floats to the top. The copper is then removed with a skimmer. At the end of this step, copper ore concentrate levels are typically between 24 and 40 percent.

After concentration, the next phase in creating market-ready copper is refining. That typically takes place away from the mine itself at a refining plant or smelter. Through copper refining, unwanted material is progressively removed and copper is concentrated at up to 99.99 percent purity, the standard for the highest-grade copper.

The details of the copper-refining process depend on the type of minerals the copper is bound with. Copper ore that is rich in sulfides is processed via pyrometallurgy, while copper ore that is rich in oxides is refined through hydrometallurgy. Read on to learn more about the copper-refining processes of pyrometallurgy and hydrometallurgy, as well as refined copper production.

How is copper extracted by pyrometallurgy? In pyrometallurgy, copper concentrate is dried before being heated in a refining furnace. Chemical reactions that occur during the heating process cause the concentrate to segregate into two layers of material: a matte layer and a slag layer. The matte layer, on the bottom, contains the copper, while the top slag layer contains the impurities. The slag is discarded and the matte is recovered and moved to a cylindrical vessel called a converter. A variety of chemicals are added to the converter, and these react with the copper to form converted copper, called “blister copper.” The blister copper is recovered and is then subjected to a process called fire refining. In fire refining, air is blown through the copper to oxidize impurities into slag; then wood is added to help reduce the oxidized copper through chemical reactions, leaving refined copper behind to be processed into copper cathode. Finally, to completely deoxidize the copper, either phosphorus is added to it to form P2O5, or the copper is cast into copper anodes and placed in an electrolytic copper cell. Once charged, the pure copper collects on the cathode and is removed as a 99 percent pure copper product.How is copper extracted by hydrometallurgy? In hydrometallurgy, copper concentrate undergoes refining via one of a few processes. The least common method is cementation, in which an acidic solution of copper is deposited onto scrap iron in an oxidation-reduction reaction. After enough copper has been plated, the copper is then further refined. The more common refining method is solvent extraction and electrowinning, or SX/EW. This newer refining technology became widely adopted in the 1980s, and roughly 20 percent of the world’s copper production is now produced via this process. Solvent extraction begins with an organic solvent, which separates copper from impurities and unwanted material. Next, sulfuric acid is added to strip the copper from the organic solvent, producing an electrolytic solution. This solution goes through the electrowinning process, which plates copper in the solution onto a cathode. This copper cathode can be sold as is, or can be made into rods or starting sheets for other electrolytic copper cells.How does refined copper reach the market? Mining companies may sell copper in concentrate or cathode form. As mentioned above, copper concentrate is most often refined using equipment at a different location than company mine sites. Concentrate producers sell a concentrate powder containing 24 to 40 percent copper to copper smelters and refiners. Selling terms are unique to each smelting company or copper refinery, but in general, the smelter pays the miner approximately 96 percent of the value of the contained copper content in the concentrate, minus treatment charges (TCs) and refining charges (RCs). TCs are charged per tonne of concentrate treated, while RCs are charged per pound of metal refined. These charges fluctuate with the market, but are often fixed on an annual basis. TCs and RCs tend to rise when there is a high availability of copper ore. Miners indicate copper concentrations, although they may be spot checked by a third party when en route to the refiner. Additionally, penalties may be assessed against copper concentrate according to the level of deleterious elements contained, such as lead or tungsten. Most smelting companies have strict limitations on permissible concentrations of impurities, and if concentrate producers do not meet these needs, they will be subject to financial penalties. Miners may also receive credits for “valuable” minerals, such as precious metals gold and silver. TCs and RCs are levied separately on these metals. Smelters generally operate by charging tolls, but they may also sell refined copper metal on behalf of miners. All of the risk (and reward) of fluctuating copper prices, then, falls on miners’ shoulders. Typically, copper concentrate is traded either via spot contracts or under long-term contracts as an intermediate product. For spot contracts, miners are paid according to the copper price at the time that the smelter/copper refinery makes the sale, not at the copper price on the date of delivery of the concentrate. For longer-term contracts, pricing is based on an agreed-upon copper price for a future date, typically 90 days from time of delivery to the smelter.

In pyrometallurgy, copper concentrate is dried before being heated in a refining furnace. Chemical reactions that occur during the heating process cause the concentrate to segregate into two layers of material: a matte layer and a slag layer. The matte layer, on the bottom, contains the copper, while the top slag layer contains the impurities.

The slag is discarded and the matte is recovered and moved to a cylindrical vessel called a converter. A variety of chemicals are added to the converter, and these react with the copper to form converted copper, called “blister copper.” The blister copper is recovered and is then subjected to a process called fire refining.

In fire refining, air is blown through the copper to oxidize impurities into slag; then wood is added to help reduce the oxidized copper through chemical reactions, leaving refined copper behind to be processed into copper cathode. Finally, to completely deoxidize the copper, either phosphorus is added to it to form P2O5, or the copper is cast into copper anodes and placed in an electrolytic copper cell. Once charged, the pure copper collects on the cathode and is removed as a 99 percent pure copper product.

In hydrometallurgy, copper concentrate undergoes refining via one of a few processes. The least common method is cementation, in which an acidic solution of copper is deposited onto scrap iron in an oxidation-reduction reaction. After enough copper has been plated, the copper is then further refined.

The more common refining method is solvent extraction and electrowinning, or SX/EW. This newer refining technology became widely adopted in the 1980s, and roughly 20 percent of the world’s copper production is now produced via this process.

Solvent extraction begins with an organic solvent, which separates copper from impurities and unwanted material. Next, sulfuric acid is added to strip the copper from the organic solvent, producing an electrolytic solution.

This solution goes through the electrowinning process, which plates copper in the solution onto a cathode. This copper cathode can be sold as is, or can be made into rods or starting sheets for other electrolytic copper cells.

Mining companies may sell copper in concentrate or cathode form. As mentioned above, copper concentrate is most often refined using equipment at a different location than company mine sites.

Concentrate producers sell a concentrate powder containing 24 to 40 percent copper to copper smelters and refiners. Selling terms are unique to each smelting company or copper refinery, but in general, the smelter pays the miner approximately 96 percent of the value of the contained copper content in the concentrate, minus treatment charges (TCs) and refining charges (RCs).

TCs are charged per tonne of concentrate treated, while RCs are charged per pound of metal refined. These charges fluctuate with the market, but are often fixed on an annual basis. TCs and RCs tend to rise when there is a high availability of copper ore.

Miners indicate copper concentrations, although they may be spot checked by a third party when en route to the refiner. Additionally, penalties may be assessed against copper concentrate according to the level of deleterious elements contained, such as lead or tungsten.

Most smelting companies have strict limitations on permissible concentrations of impurities, and if concentrate producers do not meet these needs, they will be subject to financial penalties. Miners may also receive credits for “valuable” minerals, such as precious metals gold and silver. TCs and RCs are levied separately on these metals.

Smelters generally operate by charging tolls, but they may also sell refined copper metal on behalf of miners. All of the risk (and reward) of fluctuating copper prices, then, falls on miners’ shoulders.

Typically, copper concentrate is traded either via spot contracts or under long-term contracts as an intermediate product. For spot contracts, miners are paid according to the copper price at the time that the smelter/copper refinery makes the sale, not at the copper price on the date of delivery of the concentrate.

For longer-term contracts, pricing is based on an agreed-upon copper price for a future date, typically 90 days from time of delivery to the smelter.

This is an updated version of an article originally published by the Investing News Network in 2011.

Don’t forget to follow us @INN_Resource for real-time updates!

Securities Disclosure: I, Melissa Pistilli, hold no direct investment interest in any company mentioned in this article.

Plasma Arc Furnace Investing News Network websites or approved third-party tools use cookies. Please refer to the cookie policy for collected data, privacy and GDPR compliance. By continuing to browse the site, you agree to our use of cookies.